|

|

Elías

A dasme (*) |

|

|

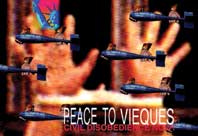

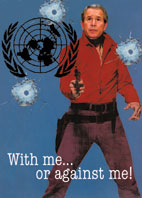

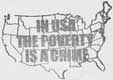

To speak of mail-art in Latin America is to speak of an art form whose origin is intimately linked to the continent’s dark period of cultural and political repression during the 1960’s and 70’s. Thou it is true that mail-art spread rapidly across the world, following the ground-breaking proposals of Ray Johnson and his interactive “Add and Pass”, brought to life in New York as an alternative response to the art work’s traditional way of production, distribution, and consumption, we can observe that in Latin America such spread responded to punctual situations with clear historical motivations rather than to mere formalist concerns. As in society at large, hundreds of artists and intellectuals were detained, tortured, vanished and/or executed by the period’s de facto governments, which made unavoidable the acts of cultural resistance on one hand, and, on the other, the perpetuation of values such as justice and liberty in their political manifestation. A labor of restoration of the social fabric in its historical framework. It is in this context where the critical and collaborative aspect of Latin American mail-art begins to show. The disappearance of Palomo Vigo, the son of Argentinean mail-artist Edgardo A. Vigo, the banishment of Chilean artist Guillermo Deisler, and the incarceration of Uruguayan artists Clemente Padín and Jorge Cerballo, just to mention the most emblematical examples of acts, among many, that drove artists to the indictment and testimonial of the dramatic reality they lived inside their respective countries. They then adapted the mail format as a vehicle of expression and communication that attempts to overcome (not always) the domineering ironclad censure. The emission of homemade rubber-stamps, the production of postcards devoid of tourist and commercial purpose, as well as the emergence of alternate press (then it was called “marginal”) such as fanzines, video art with a slant towards the documentary, and other clear-cut contestable manifestations, cemented an international circuit of creative communication that, —I dare assume— constitutes today the closest historical antecedents to the Internet. From then to the present, much water has flowed under the bridges. Latin American and World reality has significantly changed, even though the roots of old problems persist, added to new ones, that render the region highly volatile and unstable in political and economical terms. In the cultural field, the unavoidable institutionalization, and commercial absorption of the 1960’s avant-garde postures, postures that worked as the main gear or theoretical foundation of a series of artistic manifestations such as performance, video art, and mail-art, show at present a major part of these productions as lacking meaning in their messages, being repetitive or academic in their development as a language, and diminished as concerns their potential for renovation and change. This is fundamentally due to the own waning of the proposals (completely natural, of course) and the concessions to markets and money by way of some artists, that see in it a manner of “protecting” their personal practice, understood under the principles of track and prestige. In other words, the abandonment of utopia as the “leit motive” of the art practice. However, not all is so dramatically negative. Of all the alluded manifestations, it is in mail-art produced now in Latin America where we perceive with broader and inspiring clarity the “reinvention” of the avant-garde’s postulates not only from the 1960’s but also a close approach to dadaist ideas of the early twentieth century. The old dream of changing not only art, but also life, continues in force in the art and action of many mail-artists in Mexico, Argentina, Uruguay, Colombia, and Chile. As stated earlier, it is the continent’s immediate reality in its historical flux that creates the necessary conditions for a work of art to be understood more as process than as object, main feature of mail-art. From this viewpoint art is no longer a mere mirror held up to nature, but nature itself understood as prime material in the construction of the art work. The dynamics of history assumed as a creative and communication act. For way of example, when the AUMA collective (Urgent Action Mail Art) sent out its urgent action proposal “Postcards for Vieques,” (http://www.adasme.net/ArteCorreo/ViequesExpo.html), in which solidarity was requested with the puertorrican island used for sixty years as a military target range by the United States Armed Forces, in addition to the creation of an international circle of creative communication from the mailing of postcards, an indictment of a specific reality was stated in front of international public opinion, being at once chroniclers of a particular moment, laying a bet on a humanistic solution to the problem stated and vindicating the vitality of the critical meaning of art. Most of the totality of the works received and circulated by conventional and electronic mail emphasized on the trampling by the forces of power and a desire for the immediate cessation of such situation. |

|

||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

These streams of “humanistic solidarity” are the vectors that keep mail-art from its commercial absorption and institutionalization, placing it in alliance or fusion with movements of civil resistance, so necessary in this times of globalization. Novel aspect that we should keep in watch, for it gives continuity and historical identity to an art practice that is constantly threatened. From the silence of the established critics to the anchylosis and biased apathy of some artists. It is true it seems ill-timed to speak of “avant-garde art” in these postmodern times in which the lack of political and social compromise, in addition to the siren songs of mercantile neo-liberalism, practically void any effort of art criticism, but if we observe closely the leading role (in most cases, not on purpose) that the production of certain sectors that historically have been rejected by traditional circuits of art, (graffiti artists for one, college circles fanzines, or the poets, performers, and mail-art collectives that spontaneously form in the Internet) has steadily acquired, we will notice that they effectively constitute a live and dynamic example of a “first wave” or “spearhead” in the construction of new spaces of liberty and creation. That is to be avant-garde and it has to do with utopia, in Latin America there is ample fertile ground for it. (Translated by Juan Delgado) |

|||||

|

|

|

|

|