After

in 1989 at the Third Havana Biennial the articulating axis of the

general discourse the event should adopt became for the first time

a matter of reflection, it has been difficult for us organizers

to escape from a thematic scheme(1). Perhaps the

eighth edition, ope-ning in November of 2003, succeeded in tightening

at least in one of its nuclei, the supposed limits of such a model,

when under the label of Art with life we tried to distinguish some

of the operations that demonstrate such conjunction rather than

precise narratives around the subject. Collective projects such

as Isaroko, Mover las cosas, 30 Días de acción (of

the Department of Public Interventions), or proposals such as those

of Daniel Lima, BIJARI, the ENEMA collective, and the Grupo Nómada,

gave an account of it. In parallel, and according to the already

traditional scheme, other works – original, as well as recurrent

in the event at the Fortress of San Carlos de la Cabaña–

dealt with very diverse subjects, from the ample and comfortable

perspective of the universe of relations established between art

and life.

Some

time later, just in the time when the dialog aiming at conceiving

and designing the Ninth Biennial started, some of the curators became

interested in the idea of continuing to develop the possibilities

of insertion of the event in the physical and social cartography

of the city, which lead them to think on the convenience of planning

workshops that would propitiate that Cuban and foreign artists and

designers worked together, in close contact with sectors of the

population of the City of Havana. The workshops would be conceived

taking in mind, on the one hand, local needs of urban nature and,

on the other hand, problems of artistic-cultural nature, whose conflictive

knots would once again be loosened or tighte-ned through the groupally-generated

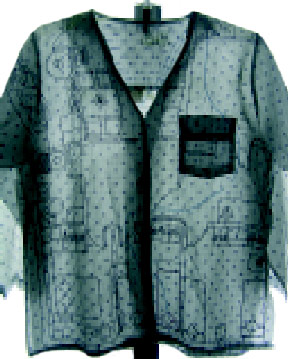

discussions and actions. But except for the alternative clothes

workshop, coordinated by guest curator Pedro Contreras, no other

took place or even went past the planning stage, because of the

lack of the essential minimum budget in some cases, and in others,

because accomplishing it required, as an old colleague of the team

said some time ago, involving many and sensitizing everybody, which

is not always possible.

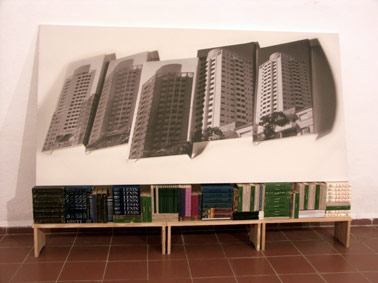

Elder

Santos (Brasil) Instalación

2006

Elder

Santos (Brasil) Instalación

2006

PHOTO:

Ximena Narea |

Thus, the workshop on urban furniture was a failure –its

purpose had been to discuss the relations between sculpture

and design of furniture as a matrix, and to invite several

artists from in the sculpture field who had explored the possibilities

of this type of objects, to produce scale models and prototypes

of viable projects for our restricted production context,

to be installed –perhaps– in public spaces of

Havana City. Another of the workshops was to be related to

the popular, abundant and varied feasts in most of the countries

participating in the Biennial. In its latest editions, some

voices had mentioned the distance of the event with respect

to the expressions of popular culture, previously exhibited

without false complexes side to side with contemporary formulations

that refer to or start from its codes and procedures(2).

It would not make sense now to go as far back as to issues

such as wire toys and Mexican rag-dolls, or to retake the

thesis of cultural appropriations and inter-crossings(3),

but it did seem attractive to explore the renewal behavior

of many of the expressions that are part of the urban culture

at the present time, some of which can find in the carnival

an agglutinin support. Thus the idea surged of linking the

workshop with the Havana carnival, preserving the best and

modifying, with constructive vocation, ideas and stereotypes

that result in the impoverishment of the visual characteristics

of such yearly celebrations. It was interesting, for example,

to retake experiences like the one undertaken by the Cubans

Omarito and Duvier in the Parrandas de Remedios, and to give

part to architects, designers and craftsmen in what would

become a laboratory sustained in the today almost abandoned

belief of the transforming capacity of art, antipodal to disillusion

and indifference.

Close

to the former, regarding to the possibility of tending bridges

towards the popular culture and of bringing artists, anthropologists

and practitioners of various disciplines together, a workshop

was conceived focusing on designing and making toys and

other objects as a form of play, with the added participation

of children and adolescents. At the same time, it was intended

to explore the behavior and the transformations of the artisan-made

toys, incorporating modern materials and urban references

for the elaboration of new prototypes, while fighting to

maintain a place within the market of practical and symbolic

goods.

The

fifth workshop was conceived with the aim of provoking a

discussion on the various modalities of projects for social

insertion through art, as well as the reciprocal acquaintance

of experiences developed by artists who live and work in

different contexts and circumstances. The challenge was

to make this workshop work, as much from the theoretical

as from the practical point of view, taking into account

that the development of an effort of articulation with communities

demands of the artist to venture into and to apprehend the

local surroundings, which requires of a period of permanence

in the field, which in turn requires of some financing (this

planted beforehand the seed of doubt with respect to its

possibilities of real concretion). Such space would facilitate,

in principle, the debate on questions of ethical, aesthetic,

educative and practical-functional character, largely decisive

for the degree of effectiveness of this type of projects

and, as well, it would invite to reflect upon the (in)convenience

of its juxtaposition to the structures of Biennials and

other curatorial initiatives, ta-king into account that

these practices generally question the limits of art as

an institutionalized exercise and that its viability, in

these cases, is proportional to budgets, authorizations

and even commitments that could favor or limit the spontaneous

unfolding of many processes. Several reasons caused this

idea to dematerialize before it got to be objectivated in

a workshop: the field investigations were this time very

limited in Africa and no curator could reach Asian regions,

where it would have been necessary to esta-blish the existence

of such practices and the ways in which they are articulated

and manifested, in order to later determine whether they

can or cannot be understood by the same keys by which they

are interpreted in the West; likewise, it was not at all

clear whether there was a budget that guaranteed the (obviously

essential) attendance of the participants, nor the communication

with a Cuban artist wishing to be appointed coordinator

of the workshop was effective.

|

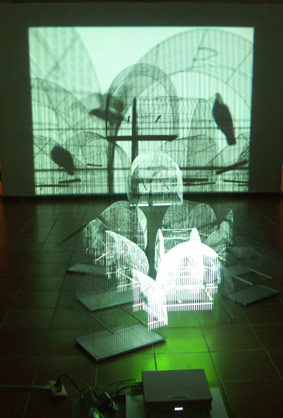

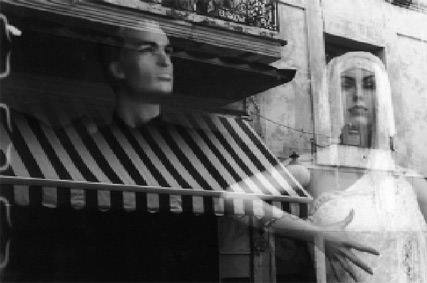

Margarita

Pineda (Colombia): Mental territories.

Margarita

Pineda (Colombia): Mental territories.

PHOTO:

CENTRO WIFREDO LAM PUBLICATIONS STAFF |

|

|

Besides

dislocating the traditional structure, these workshops could

be opened as potential nuclei to unlimited practical possibilities,

connecting to each other and establishing links with the

theoretical core of the Biennial, whose agenda did not lack

topics that would have been of common interest. By this

time, the processes of creation and exchange would have

a more relevant role, the practical aspects would displace

the expositive to a greater extent, and it would be attempted

to give continuity to a process of interaction with the

city already undertaken on previous editions(4).

Nevertheless, it would be worth asking oneself to what extent,

by this method, the Biennial would have assumed a confined

position in a dangerous –in some ways, exclusive–

localism, hardly interacting at all with the Havana context,

or if, on the contrary, whenever giving up this structure

of laboratory-workshop, it made equal sense to return to

explore urban aspects closely bound to the subject of the

city, recurrent in multiple curatorial proposals during

the last decade(5). A possible answer to

the second question could be seen between the March 27th

and April 27th of this year at the Fortress of La Cabaña

and other spaces occupied by the event... although it is

worth to notice that there were other alternatives.

After

all, the Biennial carried out only one of its workshops

and the exhibitions perpetuated its primacy, having as an

articulating nucleus the one announced as Dinámicas

de la cultura urbana [Dynamics of urban culture]. From the

beginning, some curators were shure of being able to offer

a renewed point of view about this topic –and beyond

the workshops– in relation to other international

shows such as Iconografías metropolitanas(6),

or national ones like Ciudad, metáfora para un fin

de siglo(7); others among us, however,

suscribed to the idea with a certain measure of skepticism.

The differing note allegedly consisting on that here, the

emphasis no longer would fall upon everything regarding

the urban in its dynamics, but, particularly on the culture

being born, developed and transformed within the urban territories

and their peripheral areas.

As

I see it, it would have been essential to fix beforehand

–in order to orient the search in methodological terms–

the perspective(s) from which we would approach the notion

of urban culture, considering that it has been approached

in different ways by anthropo-logy, sociology and more recently,

by cultural studies; and from that perspective, to discuss

in greater depth to what extent this complex notion, that

integrates multiple dimensions and repertoires, could act

as a thematic-conceptual axis in the work of professional

artists: “to see itself staged”; or if, on the

contrary, the Biennial had to concentrate its attention

on proposals oriented to fulfill an urban function, whose

constitution overlapped itself in the intricate weave of

relations coming to life in the city, in interaction with

the culture that developing there, exposed to constant processes

of contamination and hybridization. I talk about, for example,

proposals developed not necessarily from spatial circumstances,

but about those sites where the interests of various disciplines

converge, thus emer-ging more experimental and analytical

repertoires, or about projects with incidence on complex

urban situations, that shed light on marginalized social

groups and expressions discarded by the dominant culture,

to mention only two examples.

|

|

|

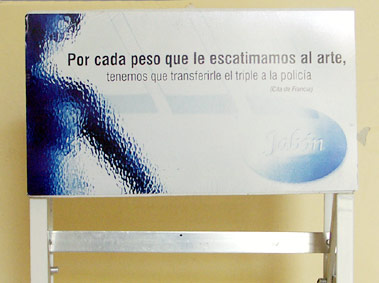

C.

Jancowski (Mexico-Germany): AGUA WASSER

C.

Jancowski (Mexico-Germany): AGUA WASSER

PHOTO:

Ximena Narea |

We also know that the selection of a subject

of reflection, able to be coherently elevated as an articulating

guideline of the discourse of an exhibition, is determined in the

first place by its endorsement by the organization. Reviewing processes

concerning passed editions, I remember how after elucidating in

a group an interesting subject –often controversial and with

sufficient potential as to support counter-discourses postulated

from the South– the way was paved for the ne-cessary exercise

showing an approximated measurement of its practical feasibility,

through the study of the archives and, even, of what had been exhibited

in previous editions of the event. In this occasion, with equal

intention and following custom, some names were thrown on the table

of discussion as previous training to the search in situ, although,

in my opinion, the exercise was not taken up to a fully enlightening

point. And in effect, shortly after, during the revision of the

material gathered after investigations conducted in a limited number

of countries, or by the means of the Internet and electronic mail,

it was noticed that it is not precisely the nexus with the Dynamics

of urban culture that best potentiates the contemporary production

of the regions involved in the Biennial or, at least, the one with

limited resources that can arrive in Havana(8).

It was thus how the span of the selection criteria had been wi-dened,

now in a definitive way, towards other parcels of the urban field.

From

the above, it could be inferred that, although during the discussions

previous to the process of selection of guests, some of the guidelines

of whatever could be placed in the area one of the “Dynamics...”,

lacked clarity on the matter. It is not less certain that during

the field research, the notion at issue tends to expand and, in

direct connection with praxis, new sources not a priori identified

by the curators can be detected; the knowledge of the context where

the artist creates allows to state how, what at a distance could

seem irrelevant, can contribute with other meanings and become data

that reveals cultural specificities. However, it becomes essential

to distinguish from the preliminary dialogs (above all, when one

attempts to focus a subject from new angles) what, because already

explored or overstated, must be immediately discarded. Let us say,

for instance, that at the Fortress of the Cabaña, considerable

segments of the exhibition showed, through photography and to a

lesser extent through video and painting, fragments of urban landscapes

focused on the architectural and physical particularities of some

cities. I am not going to stop here to analyze to what extent what

was included in them could be considered as the vanishing lines

of the ge-neral subject, which was, after all, assumed by the curators,

but the uncomfortable reiteration could not even be justified as

a conscious alert –emitted by the curators– about a

phenomenon related to fashion and to the interests of the market

–something well-known already(9)–,

nor under the argument referring to the vindication and actualization

of a traditional genre (landscape) based on the use of “new”

means –which would be another self-evident truth. An opportune

selection would have avoided unjustified re-incidences, and at the

same time granted greater visibility to the better elaborated proposals:

those that revealed, at least, more subjective relations of the

individual with his surroundings(10).

|

|

Pedro

Abascal (Cuba): Labyrinth, photographic installation

- 2006

Pedro

Abascal (Cuba): Labyrinth, photographic installation

- 2006

PHOTO:

ARCHIVO CENTRO WIFREDO LAM |

|

On

the other hand, the label “Dynamics...” had created

without doubt expectations as far as the pre-sence of a public art

developed according to the ideas of coexistence and participation,

suitable to mobilize the city around it and to again place the artistic

within a framework of wider sociocultural relations –highlighted

by Modernity as an independent entity–. Although experiences

of this character weren’t scarce, I must admit that they were

present in insufficient numbers, and not all of them did attain

the degree of ideo-aesthetic consistency that would have granted

them a considerable resonance in our metropolitan space(11).

In parallel, and agreeing with “the Third-World” vocation

of the event expressed among its founding precepts, it should no

longer contemplate actions undertaken in Havana, but in other cities

of the South, for the sake of underscoring the behaviors of these

practices when they are projected from the specificities of other

contexts. The transfer of such experiences to an exhibition of the

scope of a Biennial usually takes place through registries documenting

the processes by means of the use of photo-graphies, videos, texts,

objects, etc. Facing isolated proposals of this kind, the curators

showed a certain reluctance during the process of selection, taking

into account that not always this documentation is attractive from

the aesthetic point of view and this, sometimes together with the

scarcity of information and other times with a careless design of

the exhibition, lead to a decrease of its communicative capacity

and, consequently, to the boredom of the spectators. Thus, among

the few selected registries we could consider Oferta de empleo,

of Álvaro Ricardo Herrera (Colombia) and those corresponding

to Agua-Wasser (Mexico) and to Territorio Sao Paulo(12)

(Brazil).

|

|

Jordi

Colomer (Spain): Anachitekton (Osaka). Photography -

2004

PHOTO:

ARCHIVO CENTRO WIFREDO LAM

Jordi

Colomer (Spain): Anachitekton (Osaka). Photography -

2004

PHOTO:

ARCHIVO CENTRO WIFREDO LAM |

|

Besides,

as it could be noticed, the balance shifted this time in favor of

photography and video, which was noticeable in the prevailing disposition

of the Fortress of San Carlos de la Cabaña. Previously, and

especially from the Third Biennial (1989), installations had been

gaining presence within the the event, strengthening their protagonism

in the fifth edition (1994). Some interested people started to wonder

at that time whether the predominance of this support obeyed to

programmatic aims of curators. In fact, the conditions of self-reflectiveness

proposed by the Biennial in each edition, used to materialize in

neoconceptual proposals based on this grammar, thereof its preeminence.

It was during the Fourth Biennial (1991) when the Fortress of the

Tres Reyes del Morro was used for the first time as an exhibition

space and soon, in the fifth, the event extended to La Cabaña.

The huge dimensions, the stony and forceful character, and the memory

load these spaces hold, usually causes a strong impression on the

foreign artists arriving to exhibit, even though they beforehand

received plans and photographies of them. Difficult to “domesticate”,

and non-susceptible to become neutral containers as a docile “white

cube”, they behave in a more benevolent –and even favorable–

way, when lodging works of installation profile involving the empty

space into the structure of the artistic object, but “swallow”

or tend to turn almost invisible bi-dimensional works of small and

medium size. Their use demand, therefore, a careful museistic design

and certain conditions of display(13).

This

time, some spaces remained half-empty, unba-lanced, and the faults

in the museography accentuated the irregular character of the selection.

Besides doing without the construction of thematic nuclei, except

with limited exceptions, neither the dialog nor the efficient counterpoint

between works functioned, as neither did opportune solutions in

order to avoid the unnecessary dispersion –all things which

would have mitigated, to a certain extent, the sensations of po-verty

and imbalance. There was in all of that a quota of responsibility

concerning the curators, in addition to the delayed arrival of works,

the material absences at the last hour, and the material limitations

above described(14); add to this the ones pertaining

to those in charge of deciding upon the emplacement and –

by the way –of the permanence time of some works in the urban

space.(15)

|

|

Roberto

Stephenson (Haiti): No title, digital impression. - 2004

Roberto

Stephenson (Haiti): No title, digital impression. - 2004

PHOTO: ARCHIVO

CENTRO WIFREDO LAM |

|

Going back in time, I would say that already the

sixth Biennial in 1997 sent the first intermittent signals about

the necessity to rethink the structure of the event. Incipient attempts

of transformation have taken place in the successive editions with

partial results, achievements and errors; but the ninth edition

rang the alarm like no other, emphasizing that urgent and vital

necessity of renovation. For it, it will be essential to contemplate

not only aspects concerning the structure and the regularity of

the model, but to review its intentions and projection according

with the complexity of the changes that have taken place in the

world-wide geopolitical map, the national and international artistic

scene, and the demands and operating exigencies of new means, languages

and ways of operationalization; all that, without losing sight of

the restrictions that the accomplishment of an international Biennial

implies from our own here and now: that is the challenge. Through

the years we have received very objective criticisms –which

we always receive gratefully– as well as judgments that denote

a superficial approach to the art of the regions that the Biennial

focuses on, and an ignorance or underestimation of the conditions

under which it takes place. The present circumstances are not the

same ones that caused the irruption of the event in 1984, as the

interests to conciliate are not the same either. To project utopias

never was the most difficult thing to do –the greatest challenge

lies in making it viable to attain their materialization. In this

way, any criticism or suggestion is welcome.

NOTES

1

The Third Biennial of Havana was articulated around the

coordinates Tradition and contemporaneity. It is worth to

explain that the interest was in no way focused on emphasizing

a notion of constructed cultural identity only from the

perspective offered by this polarity – a reductionistic

criterion that would have only entailed the construction

of a pseudo-identity. Rather, the event called upon the

attention of one of the multiple characteristics qualifying

a significant area of the contemporary production of the

countries of the so called Third World.

2

In the Third Biennial, whose subject was Tradition and contemporaneity,

as mentioned above, the exhibitions Juguetes de alambre

africanos, Bolívares en talla de madera and Muñecas

mexicanas, among others, caused the connivance in a “legitimizing

space”, of sophisticated works emanated of the so-called

cultured art, with living expressions of popular art (not

forgetting others that have arisen from the contamination

of both registries), thus marking its stance in this debate.

With similar intentions, the exhibition Arte del Pueblo

de Weifang, which reunited an important collection Chinese

kites, was sown at the IV Biennial.

3

Apropiaciones y entrecruzamientos were one of the five nuclei

of exhibitions that under the general subject Art, society

and reflection, were presented at the Fifth Biennial of

Habana in 1989. The show did not exalt those works that

resort to the quote, the paraphrase, the parody, and to

postmodern variations of Art History’s masterpieces,

but proposals where connections between groups of symbolic

production of diverse sign co-exist in the Asian, African

and Latin American countries. This exhibition reunited works

that reflected an interest in expanding the limits of the

potentially adaptable, establishing conscious and unbiased,

nexuses of differentiated nature between the traditional

and local popular culture, the referents of primitive and

pre-Hispanic cultures, the lexicon that emanates of the

mass media and the symbolics associated to the market.

4It

is important to point out that this would not be the first

time that the Biennial would call for the participation

in workshops, although in this opportunity they would play

a wider and more protagonic role within the general structure

of the event, no longer because of the number of workshops,

but because they would attract a very significant portion

of the list of guests. For more information on the workshops

carried out in previous editions, see the catalogs of the

Third and Fourth Biennials.

5

In fact, not only the city has confirmed its presence as

a subject in exhibitions, but also the urban itself, if

we considered that, according to the distinction established

by Henri Lefebvre ...the city [ is ] present, immediate

reality, practical-sensible, architectonic data and, on

the other hand, the ‘urban’ [ is ] social reality

composed of relations constructed or reconstructed by thought

(quoted by Celia Ma. Antonacci in Grafite, Pichação

& Cia São Paulo: ANNABLUME, 1994, p. 31).

6

Metropolitan iconographies was the subject of the XXV Biennial

of São Paulo in 2002. Its curator, Alfons Hug, said

about it that ...it hardly refers to the image of the metropolis

in contemporary art, but also to the way by which the currents

of urban energy influence the work of contemporary artists,

among other topics (Hug, Alfons. “XXV Bienal de São

Paulo”. Revista del Instituto Arte das Américas,

no. 1, July-December 2003)

7

Ciudad, metáfora para un fin de siglo, functioned

as an articulating axis of the II Salon of Contemporary

Cuban Art celebrated in 1998, under the curator Caridad

Blanco and organized by the Center of Development of the

Visual Arts of Havana.

8

More ambitious, powerful and actually more oriented along

such a path, projects like Caja lúdica (Guatemala),

Nortec (Mexico) and Territorio São Paulo (Brazil),

could not participate due to financial limitations. The

Nortec group, for example, fuses in its presentations multimedia,

typical electronic northern and band music, videoclips,

graphical and fashion design, and expressions of the visual

arts in general, to develop a production immersed in the

reality of the border between Mexico and the US, revealing

the crossings and transferences that are part of the weave

of the urban culture in that enclave. Territorio Sao Paulo,

on the other hand, was the name given to a project designed

specially for the Biennial of Havana by twelve art groups

that work in the streets of the Brazilian city: Cia. Cachorra,

C.O.B.A.I.A., Bijari, Contra Filé, TRancaRUa, etc.

In general, their actions promote the reflection upon urban

situations related to violence, exclusion, and the operations

of “social hygiene” of downtown areas, the excesses

of real estate and the processes of gentrification, among

other subjects. They use tools from other disciplines like

the anthropology, sociology and demography; resources from

music, the scenic arts, literature and the audio-visual;

and codes and strategies from social activism and the mass

spectacle, synthesized at a higher level of symbolic elaboration.

9

Artists such as the Germans Thomas Ruff and Günter

Förg, as well as the French Jean-Marc Bustamante, are

between the initiators of this fashion in the 90s, which

has circulated and gained adepts in different latitudes.

10

Beyond the tautological character of the collection exhibited

at La Cabaña, certain successes could be perceived,

however, through precise proposals, such as Arquitectura

del vacío by Javier Camarasa (Canary Islands), who

through an intelligent plastic solution (a fine neon light

fragmented in two the projection screen as a line dividing

and ordering time) juxtaposed two video recordings of the

same territory, taken in different stages, to signify the

devastating avalanche of real estate tourism-related enterprises

on a virgin nature, now turned into the background of motley

architectonic complexes. Anarchitekton (four simultaneous

projections) by Jordi Colomer (Spain), showed the form in

which the culture of marketing puts its mark on the architecture

in Osaka up to the point of annulling it, or how the inhabitants

of Brasilia draw up, with their everyday transit, the functional

caminhos do desejo not projected by Lucio Costa in the Pilot

Plan of that city (among other commentaries). In addition,

it is worth to mention the work of Michel Najjar, which

glimpses the effect of Telematics in the iconic representation

of the landscape of the future. Less attached to architectonic

references, other photographic proposals were dedicated

to emphasize new elements integrated into the physical and

social landscape of large cities, but in many cases by paths

already worn out by photography, or without excellent aesthetic

results. In an opposed sense to this evaluation, the collection

of digital photos by Stephenson Robert (Haiti) would stand

out, which depicts, together with the deteriorated architecture

of some areas of Port au Prince, the ethnic and psychological

profile of some of its inhabitants, in close relation with

an everyday life of precarious and multitemporary character;

or Laberinto, by Pedro Abascal, that associates to Walter

Benjamins idea of the city as an ...accomplishment of the

old human dream of the labyrinth, treated here from the

non-distinction between image and reality, in the fragmented

visual landscape of the contemporary large city.

11

Beyond the tautological character of the collection exhibited

at La Cabaña, certain successes could be perceived,

however, through precise proposals, such as Arquitectura

del vacío by Javier Camarasa (Canary Islands), who

through an intelligent plastic solution (a fine neon light

fragmented in two the projection screen as a line dividing

and ordering time) juxtaposed two video recordings of the

same territory, taken in different stages, to signify the

devastating avalanche of real estate tourism-related enterprises

on a virgin nature, now turned into the background of motley

architectonic complexes. Anarchitekton (four simultaneous

projections) by Jordi Colomer (Spain), showed the form in

which the culture of marketing puts its mark on the architecture

in Osaka up to the point of annulling it, or how the inhabitants

of Brasilia draw up, with their everyday transit, the functional

caminhos do desejo not projected by Lucio Costa in the Pilot

Plan of that city (among other commentaries). In addition,

it is worth to mention the work of Michel Najjar, which

glimpses the effect of Telematics in the iconic representation

of the landscape of the future. Less attached to architectonic

references, other photographic proposals were dedicated

to emphasize new elements integrated into the physical and

social landscape of large cities, but in many cases by paths

already worn out by photography, or without excellent aesthetic

results. In an opposed sense to this evaluation, the collection

of digital photos by Stephenson Robert (Haiti) would stand

out, which depicts, together with the deteriorated architecture

of some areas of Port au Prince, the ethnic and psychological

profile of some of its inhabitants, in close relation with

an everyday life of precarious and multitemporary character;

or Laberinto, by Pedro Abascal, that associates to Walter

Benjamins idea of the city as an ...accomplishment of the

old human dream of the labyrinth, treated here from the

non-distinction between image and reality, in the fragmented

visual landscape of the contemporary large city the Portal

del Cine Yará, in Havana. Located just in between

art and anthropology, its collection consists of voluntary

donations of people that live or temporarily visit the sites

where it is located, and translates, in the words of “its

guardians”, the spirit of the barrio that welcomes

it. Margarita Pineda (Colombia) on the other hand, walked

through markets, squares and other anodyne sites of the

city, attempting in her exchanges with the the passer-byes,

the emergency of new maps based on practices and daily rituals

enrolled in the urban experience, outlining rather subjective

territories, not determined by geography or politics.

12

Oferta de empleo was a project developed in the Mexico City

during a two-year stay of the artist. Its presentation in

Havana landed halfway between a work of author and a record,

without managing to transmit with clarity all the stages

and actions of the process. Agua - Wasser, however, conveyed

the real dimension of a collective project made in the same

City, through a moderate and properly designed version by

the curators Edgardo Ganado and Daniela Wof, which included

photographies, vi-deos, texts, scale models and other registries

on facilities and interventions made in public whose past

and/or present have a relation with water, an element that

marks the cultural history of a lake city today turned one

into a dried metropolis.

13

In the V Biennial, for example, even though most of the

exhibited works at the Fortresses of the Morro and the Cabaña

had not been conceived as interventions on the architectonic

space, the facilities showed effectiveness as far as the

handling of the space and to the advantageous use of their

intrinsic qualities in the search of certain effects. It

even happened that the dramatic aura and the communicative

force of some of those works, notably decreased when they

were exhibited later at the Ludwig Museum in Aachen, as

it was perceived by colleagues who were involved in the

assembly work.

14 As

I explained before, financial difficulties caused critical

absences in this Biennial, such as the those related to

the above mentioned projects Caja Lúdica, Territorio

Sao Paulo, etcetera, and to the participation of Brazilian,

African and Asian artists. Likewise, such difficulties prevented

the production and/or transportation of some works, which

ended up being replaced by others, or being exhibited in

poorer and inconsistent versions, thus causing the above

mentioned disadjustments.

15

The disagreements around the temporary permanence of Havana

Gold of the FA+ duo, and the location of the sculpture of

Reynerio Tamayo demonstrate a lack of understanding on the

form in which some contemporary practices operate. The golden

patina imposed by FA + to preterit elements of the urban

surroundings, with the purpose of giving them class in the

distracted or hurried eyes of the city dweller, was covered

with black painting just a short time after it had been

applied, and the sculpture of Tamayo, conceived for the

confrontation with its referent on the road where vehicles

circulate, was confined to one of the gardens of the Cabaña

and exhibited as a conventional sculpture.

|

|