|

The

poisonous gift of ‘First World’ aid after the event of terror:

|

|

|

Stephen

Morton

University of Tampere, Finland

|

After

the attacks on the World Trade Center of September 11, 2001, the co-operation

of General Musharraf, the leader of Pakistan, in the United States war

in Afghanistan led to the removal of Pakistan from the U.S. State department’s

list of countries that sponsor terrorism, and the resumption of IMF

credit and debt relief to Pakistan. In response to this shift in geopolitical

relations between Pakistan and the US after September 11 2001, Alia

Hasan-Khan produced a series of small, yellow dessert boxes modelled

on the food packages that were randomly dropped from US military planes

flying at a high altitude over Afghanistan in October 2001. The original

US food packages contained instructions in English, French and Spanish:

languages which are not widely spoken or understood in Afghanistan.

These US food packages also displayed a diagram of how to eat the food

ration of 2200 calories contained inside the box, which included items

such as peanut butter and jelly, bean salad and shortbread; all of which

are unfamiliar to the majority of the Afghan people. What is more, these

food packages resembled in shape and colour the small, yellow cluster

bombs that were simultaneously dropped by the same US military planes

over areas of Afghanistan that were already littered with around ten

million unexploded land mines left over from the war with Russia. The

perilous consequences of the US government’s cynical aid campaign

during the attacks on Afghanistan thus prompted the US military to release

a radio broadcast emphasising the difference between the food packages

and the cluster bombs-

|

|

|

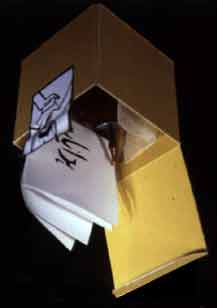

In

Gift Hasan-Khan inverted the geopolitical structure of ‘First world’

aid to ‘Third world’ countries by ‘donating’ fake

food packages to an American audience as part of a series of lunch time

seminars, about the US response to the terrorist attacks, held in the

financial district of Lower Manhattan. On the outside of each yellow

dessert box was an untranslated Urdu inscription, and a diagram instructing

the target-subject how to eat. Inside each box were more Urdu instructions

and a fake explosive device made up of gulab jamun (a piece of dessert

made with sweet curdled milk) with wire and hardware inserted inside

of it. By concealing such a device within the packaging of a ‘Third

world’ gift, Hasan-Khan foregrounds the paradoxical relation of

violence that underwrote the gift economy of US Aid to Afghanistan in

particular, and of ‘First world’ financial aid in general.

Instead of providing the means for economic independence, ‘First

world’ development loans to nations in the global South continue

to perpetuate a relation of economic dependence on First world banks

and industry-rich donor countries in the North. In the case of the US

aid program during the war in Afghanistan of 2001, as Hasan-Khan powerfully

demonstrates, the US military aid program did not even provide short-term

relief for Afghanistan’s civilians; instead it placed their lives

in further danger.

.

|

|

|

Yet

Hasan-Khan’s fake devices refuse to simply represent a tragic stereotype

of postcolonial subjectivity. By imitating the visual rhetoric of a

terrorist attack in public spaces, Hasan-Khan constructs a carnivalesque

space which encourages viewers to question the rhetoric of terrorism

and its economic and geopolitical agenda. Without denying the violence

of state democracies, extremist religious groups and military regimes

in Pakistan, the recycled devices also encourage the viewer to think

responsibly and critically about the violence which is historically

embedded in the western-based discourses of universal human rights and

representative democracy: discourses which are increasingly tethered

to the extension of economic dependency on global financial organisations

such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund. In doing

so, Hasan-Khan refuses to simply perform the role of postcolonial-migrant-artist-as-native-informant

in the United States art world.(1) Instead she articulates

the global economic conditions which foreclose the perspective of many

subaltern women in the global South whose debt and dependency —

either directly or indirectly — sustains the resource hungry lifestyle

of the North in the fabric and siting of the devices themselves.

|

1

In this respect, Hasan-Khan’s work might be read as a riposte to

Hal Foster’s model of the ‘Artist as Ethnographer’, a

model which perhaps forecloses the perspective of the native informant.

By refusing to perform the role of postcolonial-migrant-artist-as-native-informant,

Hasan-Khan also refuses to simply represent the (im)possible perspective

of the contemporary native informant, who Gayatri Spivak identifies

as ‘the poorest woman in the global South’. See Hal Foster

‘The Artist as Ethnographer’ in The Return of the Real Cambridge,

Mass. MIT, 1996: pp. 171-204 and Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak A Critique

of Postcolonial Reason: Towards a History of the Vanishing Present Cambridge,

Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1999: 6..

|

| |

|

| |

|

| Heterogénesis

Revista de artes visuales * Tidskrift för visuell konst

Box 760

220 07 Lund - Sweden

Tel/Fax: 0046 - 46 - 159307

e-mail:

heterogenesis@heterogenesis.com

|

|